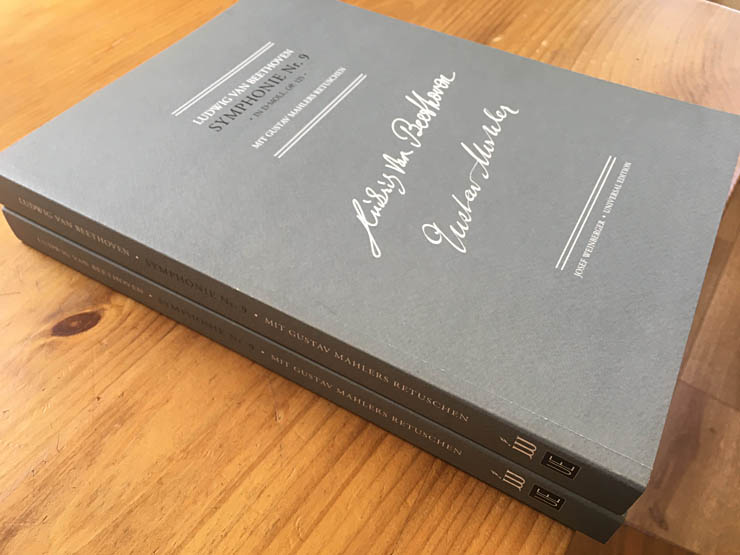

Gustav Mahler conducted Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on ten occasions: in Prague, Hamburg, Vienna, Strassburg and New York. For the last seven of these performances he prepared and used his own score and orchestral parts. I have transcribed and edited these materials...

Interpreting the First Movement of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony

The Sleighbells (Schellen)

Mahler introduced several new instruments to the symphony orchestra. Among them were the sleighbells (Schellen) that are used in his Fourth Symphony. Pitched sleigh bells had been used before (for instance, in Mozart’s German Dance, KV 605, No. 3); but Mahler’s are unpitched and there are different ideas about how they should sound. According to Baines (Oxford Companion to Musical Instruments), sleigh bells come in various sizes — as large as 10 cm across. Mahler did not specify the size in his score, and used his own set of bells when he conducted the work; though he gave a clue that they should be small when he referred to the instrument as a Schellenkappe or fool’s cap and bells in conversation with Natalie Bauer-Lechner. In the orchestra the bells are usually mounted on a strap, which is held in one fist, upon which the other fist is pounded

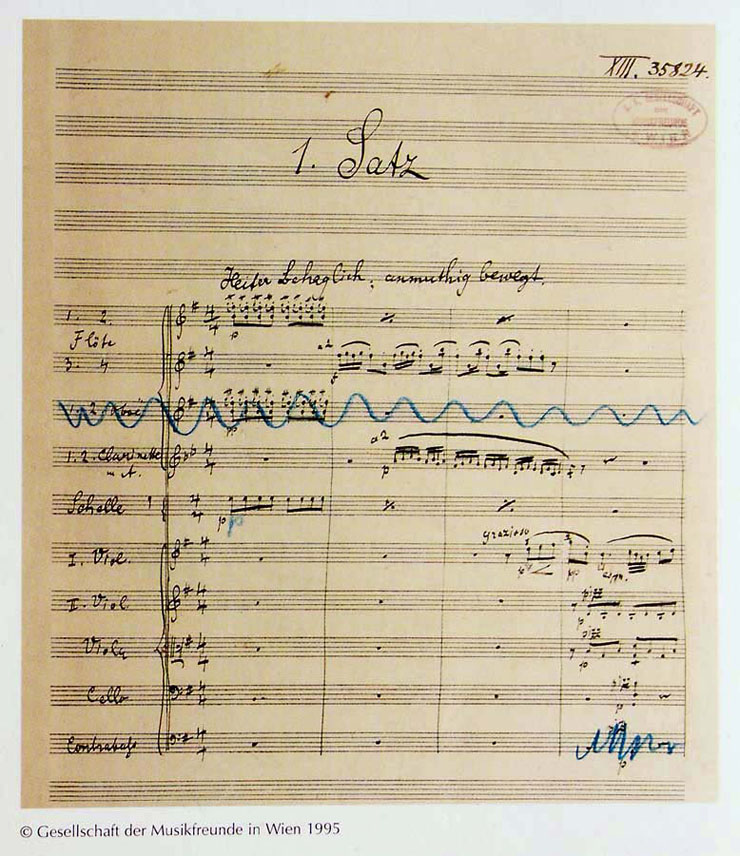

As can be seen in the manuscript reproduced above, Mahler originally marked the sleighbells and the flutes piano, and the oboes pianissimo. Before the work went to print he removed the oboes and reduced the level of the sleighbells to pianissimo, so that they would not overbalance the flutes.

In 1904, Mahler conducted his symphony with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, and it may be that the bells used there today produce the sound that Mahler had in mind. The recordings below give an idea of the different-sounding bells that have been used. They represent the instruments used in the three orchestras that played the work with Mahler — two more Concertgebouw recordings of the opening may also be heard lower down the page — plus a sample of the brighter-sounding bells used on many of the English recordings.

Vienna Philharmonic / Walter, Salzburg, 24 August 1950

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Solti, 20/21 February 1961

New York Philharmonic / Bernstein, 1 February 1960

Philharmonia Orchestra / Kletzki, 2 April 1957

The Tempo Markings

Mahler’s manuscript full score has at the beginning Heiter behaglich, anmuthig bewegt (cheerfully contentedly, charmingly animated) and this continues for the first 31 bars. In the published version, the basic tempo of the movement is given in bar 4 as Recht gemächlich, which can be translated as Rather leisurely. The first bar, however, is marked Bedächtig, nicht eilen — slow (deliberately), do not hurry. Conductors continue to disagree over the meaning of these markings.

Mahler added metronome marks to an early printer’s proof: crotchet (quarter note) = 88 at the beginning, and crotchet = 76 for bar 4. Though these did not make it as far as the first edition, Mahler would not have changed his ideas radically, and the concept of the beginning being slightly faster than the main tempo is one that makes sense.

The Ritenuto

A further cause for disagreement is in the interpretation of the end of bar 3. The clarinets have the instruction poco rit. and the first violins Etwas zurückhaltend, which may or may not mean the same thing. But the flutes and sleighbells have no indication of this at all. Despite the fact that similar instructions reoccur in the clarinet and violin at the end of bar 76, most conductors have assumed that Mahler made a mistake and intended that all the instruments slow down together. Among them it is notable that all three of the conductors on record who were most closely associated with Mahler observe a general ritenuto for all the instruments. Of these, Mengelberg heard Mahler rehearse the work with his own Concertgebouw Orchestra and then conduct it twice in the same concert on 23 October 1904; and Walter almost certainly heard him conduct it in Vienna on 12 January 1901. We have heard Walter above, and Klemperer may be heard at the end of the page. Mengelberg’s performance took place 35 years after he heard Mahler conduct it, which may explain his excessive ritenuto.

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Mengelberg, 9 November 1939

Few conductors allow the flutes and sleighbells to continue undisturbed in tempo, among them Bernstein in his later recording, and Klaus Tennstedt (not illustrated).

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Bernstein, 24-26 June 1987

The Basic Tempi

Mahler probably abandoned his metronome marks because he felt that he had specified the tempo better in words. Clearly he did not want the opening of the movement to sound rushed, but felt that a range of tempi could be made to work. Most conductors start faster than the tempo they adopt for the main theme, but some tempi are a long way from Mahler’s metronome marks and do not fit his description. Two such cases are provided by Boulez and Tennstedt, who choose M. M. 100 ... 92 and M. M. 98 ... 87 respectively. Bernstein (in his earlier recording) and Haitink both start at M. M. 82, which does not seem too slow, falling to M. M. 78 and 73 respectively for the main theme. Bernstein’s later recording is a little faster with less difference between the two tempi (M. M. 84 ... 80), and even Klemperer’s tempi (M. M. 76 ... 73) work (recorded example at the end of the page).

New York Philharmonic / Bernstein, 1 February 1960

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Bernstein, 24-26 June 1987

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Haitink, 25 December 1982

The Cleveland Orchestra / Boulez, April 1998

London Philharmonic Orchestra / Tennstedt, 5 May 1982

Mahler’s Bowings

More than any composer before him, Mahler was careful to specify in detail how almost every note of his music was to be played, and this detail extended to the bow strokes used by the string instruments. His brother in law, Arnold Rosé, was concertmaster of the Vienna Philharmonic and would undoubtedly have approved all of the bowings for the works that Mahler conducted, many of which he himself determined for Mahler. Many of the bowings printed in Mahler’s scores are ignored by orchestras. A good example is given in bar eight of the Fourth Symphony. Mahler wants the dotted quavers to be held long.

Chailly’s recording demonstrates how this phrase is most often played.

Concertgebouw Orchestra / Chailly, September 1999

Klemperer, Walter, Solti and Britten are among the few who respect in this passage the bowing of one of the greatest masters of instrumentation.

Philharmonia Orchestra / Klemperer, 4 April 1961

Another example of Mahler’s imaginative string writing is given here.

Rev. 11 Dec 2018